This Essay is part of MA Art and Design (Illustration) research on Illustrating music. It discusses the relations between musical aspects and artworks. By artwork I am referring to visual presentations such as drawings, illustrations or paintings. The thread of this paper is to explore territories of illustration and music in ways to deepen the understanding of how visual mark making corresponds to aspects of music.

The main focus point of this essay is painting, where music is an important inspiration and source of methods used in the art works. I introduce the topic through three visual presentations from different decades of the 20th century as follows: A painting from Paul Klee (1879-1940); Alter Klang (1925), a visual music score from Earle Brown (1926-2002); December 1952 (1952) and a visual listening score (1970) of György Ligeti’s (1923-2006) composition Artikulation (1958) from Rainer Wehinger.

Concerning any arts, general challenge is in defining relations between them. Indeed, together music and visual arts have been under observation and discourse for centuries. In fact, painters such as Klee, Delaunay, Kandinsky, and composers such as Debussy, Schönberg and Stravinsky, were alternately under the influence of each other, and took the inspiration and explored the concepts of art mediums to seek and identify structures and forms in their own practices in 19th and 20th century. However, one might ask, why or how should we find the relations between different arts, as it might be obvious music and painting are different? Yes, they are different in sense that the content that music expresses alone differs from painting; music’s sensory content is sound whereas the contents of painting are colour and forms for traditional thought. (Morton & Schmunk 2000; Dennis 1966)

Thinking about the fundamental characters of music, there are other aspects we should point out. Music is something invisible, which operates through our sense of hearing; basically it is sound waves, which are repeated clutters of air particles; our eardrum response them and translate them into electronic signals and then send to the brain for decoding (Vella 2000: 38). We can also consider music as temporal art where it has it’s realm or existence in time territory. Having mentioned that, it is relevant to note that it has an appearance outside of time as well, for instance, in the form of notation. (Adorno & Gillespie 1996)

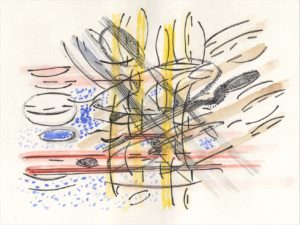

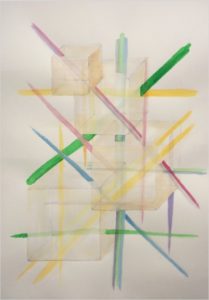

One of my experiment where the notation is taking out of context. Watercolor and Fiber-tip pen on 200g Paper, A5

Going forward and describing fundamentals of visual arts, unlike music, a painting works using two-dimensional space, which can be characterised as a spatial art. A painting is a static simultaneous object, which consists of elements that exist next to each other in surface space. It is a reworking of a space, and the creation process is carried out in time. In order to create lines of drawing one will create movements of points. Indeed, in ways how lines are organised, form elements on surface. (Rawson 1987; 15) (Adorno & Gillespie 1996; 66-69)

What explains relations between music and painting? We relate to things through the different senses, and we create the reality combining the information we receive through them. We don’t distinguish between senses of the world such as taste or touch, they are working together. Music and painting works through different senses, hearing and sight, but at the same time they share something, that is feeling. (Henry 2009) In other words, both the visual and audible perception evokes feelings. As Halliday describe, arts echoes our own subjective life. It reflects our feelings (Halliday 2013, 22).

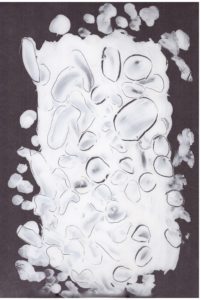

An experiment; light vs. shadow: reflection. Acrylic paint on acrylic sheet.

An experiment; light vs. shadow: reflection. Acrylic paint on acrylic sheet.

But the true connection between music and visual arts is not feeling, rather it is the outcome. The connection can be found profoundly with their language. It’s not the language in the sense of linguistic terms. As it may be obvious music and visual arts share a lot of vocabulary together, for instance, tones of music and colour, or rhythm in music and paintings. (Dennis 1966). Even though these disciplines share the same words; it does not exactly mean the same aspects. The both have their own characteristic way to convey messages.

Music and painting speak the language of how they are constructed. That is, the connection, the fundamental, is how the space, temporal or spatial, is planned, organized and used. However the methods used in music differ from those used in painting; when music deals with different pitches, melodies, harmonies, which are carried out in different rhythms and with different instruments, paintings use different colours, strokes, shapes with different materials and surface sizes. (Adorno & Gillespiel 1996:71) In other words, music and paintings have their own methods. Indeed, Adorno and Gillespie (1996:68) and Rawson (1987:195-197) suggest that operating with individual colour qualities means the same thing that composers operate with individual tones. And these methods are the base for the language that has arisen and the feelings that are evoked from artworks.

Tracking musical structures. Watercolor and pen on 300g paper, A1